By Michelle Rotuno-Johnson

Smooth coat otters clamor for a snack at Phnom Tamao. By Michelle Rotuno-Johnson

1. Tigers like the smell of Calvin Klein

This was not the first or the most profound thing I learned on my tour of Phnom Tamao Wildlife Rescue Center, but the fact stuck to me like a cotton t-shirt on a hot day in Cambodia.

My colleague Aaron and I toured this wildlife rescue in May, with the expert help of guide Niki Leroux, a native of Canada, and the patience of a fellow named Yim, who agreed to drive us to and from Phnom Penh and around the preserve.

(Below are photos of Aaron and me. Please do not let his scary tiger face or my sweaty selfie face

frighten you.)

frighten you.)

(left) Aaron's very best tiger face. (right) Me, taking a selfie with one of many monkeys who roam Phnom Tamao. By Michelle Rotuno-Johnson

Niki works with Wildlife Alliance, a group that strives to save animals from the exotic animal trade and release them into the wild. Phnom Tamao is owned by the Cambodian government and staffed by non-governmental organizations, she told us. Niki said the sanctuary was founded in 1995, and Wildlife Alliance became a partner in 2001. Another NGO called Free the Bears works actively at Phnom Tamao to care for vulnerable sun and moon bear populations.

Phnom Tamao is home to more than 100 species of animals, all housed over 6,000 acres of forest (according to its website). Aaron and I saw otters, deer, macaques, gibbons, elephants, tigers, leopards, sun and moon bears, binturongs (aka bearcats), civets, porcupines, jackals, wild pigs, an owl, and a hornbill -- a list that is extensive, but not totally exhaustive.

At 10am on a Tuesday, there were not many people driving or walking the dusty paths through the sanctuary. Two monks and a tour guide were visiting the sun and moon bears as we walked through, I spotted a tour bus, and we saw a Cambodian family wandering by the tiger exhibit.

Oh--back to those big striped cats and their perfume.

(left) Toto taking a lap in his enclosure. By Aaron Atkins. (right) Jerry having a nice nap on a hot day. By Michelle Rotuno-Johnson

Very early in our tour, we visited Indochinese tigers Toto and Jerry.

Niki told us the first tigers came to Phnom Tamao around 2001, but have all died -- she said tigers live about 12 years in the wild, and 18 years in captivity. Toto (male) and Jerry (female) are around 6 or 7 years old.

“There’s a zoo called Safari World which is...not so great,” Niki said, and I got the distinct impression this was an understatement. “And they have lots of tigers, so the government made a deal with the guy to bring (some) here.”

We watched as Toto prowled slowly around his forested enclosure and took a luxurious dip in his pool. Niki mentioned, quietly, that there are no wild tigers left in Cambodia. The last known sighting of one was in 2009.

“There might be one or two hiding in the Cardamom (Mountain)s or somewhere in the northeast, but no one’s spotted them,” she said, and told us she heard one tiger is worth between $100,000-200,000 in U.S. Dollars.

“Claws, whiskers are good luck charms. Bones, blood for...traditional medicines, the penis is an aphrodisiac, the skin and head (are) a status symbol.”

Niki shows us the bottle of perfume that tigers enjoy quite a lot. By Aaron Atkins

Behind a gate with a tiger painted on it, there were cages with sturdy iron bars where the keepers can get a closer look at the big cats. Aaron noticed some yellow liquid in a Calvin Klein perfume bottle and asked Niki about it, jokingly, as if he couldn’t imagine there was actually perfume in there.

But as it turns out, Jerry the tiger likes the smell of it, and will rub her face on the bars where Niki or another keeper has sprayed it. Niki spritzed some in the cage and coaxed Jerry to come inside while Aaron and I continued to ask her questions about the tigers.

Both tigers wandered in as we stood back there, and Niki called to them softly, chirruping a “hello” and even reaching out to scratch them as they brushed their big bodies against the metal bars. She seemed to know each animal by name and have a distinct call for each.

Jerry stretched out to take a nap, her massive paws just a few inches from where I crouched safely on the other side. It was the closest I had ever been to a wild animal (up until about 20 minutes later).

I marveled at the majestic cat as she took deep breaths, panting a bit in the heat, twitching to flick flies off of her ears or tail. I wondered what her life was like before this.

I would learn, quickly, how many of these animals left a life of abuse, danger, and/or overwork to come live in the sun at Phnom Tamao.

2. Elephants can be quite sassy

One of Phnom Tamao’s best-known residents is Chhouk, an elephant, whom WIldlife Rapid Rescue Team members picked up in 2007 when he was just a calf. Young Chhouk (the name means “lotus”) was thin and badly injured, and part of his leg had been severed by a trap.

When we saw Chhouk, he was walking around confidently on a prosthetic foot. Niki says Phnom Tamao staff check his leg twice daily, and Chhouk is used to keepers taking his prosthetic foot on and off. If the foot is uncomfortable, he can even take it off himself. We tossed him carrots and bananas through the gate, as Niki said he is a bit too aggressive for strangers to hand-feed.

(top left) Chhouk, sauntering through the field. By Michelle Rotuno-Johnson (top center) A close-up of what Chhouk's prosthetic foot looks like. (top right) Chhouk looking for a snack. (bottom left) A close-up with sweet Jamram. (bottom right) A close-up with sweet Jamram. By Aaron Atkins

The elephants each had their very own personalities, Niki told us while we backed away from a female named Lucky who is known to throw dirt at people if she does not get her way.

“She’s a diva,” Niki said simply, sharing that Lucky once threw a rock at park director Nick Marx’s car, apparently because he did not say hello to her. She has also been known to throw dirt at people who walk by with a snack but do not give her one.

In my humble opinion, Lucky has earned the right to diva-like behavior. She survived as an orphan before she was picked up by Phnom Tamao agents, and has since become a well-loved ambassador for the wildlife rescue, as well as a surrogate mother to Chhouk. In 2015, Niki said, Lucky contracted elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus (EEHV), which is highly fatal to Asian elephants. Lucky lost part of her ear to the herpes virus, but has almost recovered fully.

So, as I said, I couldn't blame her for being sassy. All the same, I watched her closely to make sure she didn't throw dirt at me.

Aaron meets Jamram and gives her some banana while I coo at her in the background. By Michelle Rotuno-Johnson

A female elephant, Jamran (meaning “prosperity”), allowed an awestruck Aaron and I to pet her. She took offerings of carrot and banana right from our hand with her trunk -- it felt a little bit like I had gotten elephant snot on my hand, but I honestly didn’t mind. At what other point in my life would I ever be able to feed an elephant, or even touch one? Elephant snot almost seemed like a blessing of sorts. It was surreal to stand feet away from her, looking into her beautiful brown eyes as I felt her rough skin.

Jamran was gentle, but Niki advised us to stay away from the gate when Sakor, the male elephant in her enclosure, got too near to us (Sakor means "ocean").

Deforestation and increasing land development pushed both Jamram and Sakor into human areas to look for food, as their natural homes had become too fragmented and vegetation too scarce.

Lucky, who lost part of her ear to a herpes infection. By Aaron Atkins

You can read more about the elephants of Phnom Tamao on the sanctuary's website.

Click here to visit.

Click here to visit.

3. Humans are the problem, but they can also be the solution

This third "lesson" I learned at Phnom Tamao was one that became most apparent when we visited

the nursery.

the nursery.

((left) Aaron interacts with a muntjac deer at the Phnom Tamao nursery. (middle) A baby civet. (right) Two baby pileated gibbons. By Aaron Atkins

At the nursery, Phnom Tamao cares for baby animals rescued from the pet trade. We saw some of the newest arrivals first. A small civet, who had just been rescued, looked up nervously from inside a plastic tub. An oriental hornbill and a brown wood owl perched in their own cages.

Tiny pileated gibbons and long-tail macaques swung around their areas, gathering close to the front to peer at us and even give a hesitant smile. Niki explained that the little primates have seen people smiling at them, so they mimic the gesture. The little ones at the front of the park were the size of my forearm or smaller.

Keepers will bottle feed the most vulnerable baby animals every few hours, and hopefully release them back into the wild near Angkor Wat or in one of the designated release sites around Cambodia. Niki also works at the release center in Koh Kong.

The nursery area housed plenty of other animals in larger enclosures: more macaques and gibbons of varying varieties, Muntjac deer, and otters.

A young macaque, rescued from the illegal pet trade, comes close to say hello. By Aaron Atkins

Over a lunch of fried rice and noodles, Niki continued telling us about Phnom Tamao. She said the rescue’s first charge is to promote conservation and provide a zoo experience for visitors. The second is to rehabilitate and release the animals.

“The end goal is to release, but obviously some can’t be due to physical or psychological damage, so they’re just given a permanent home. We don’t euthanize and we don’t turn anything away. ...the end goal would be that the government fully takes it over and guides it in a conservation-minded way.”

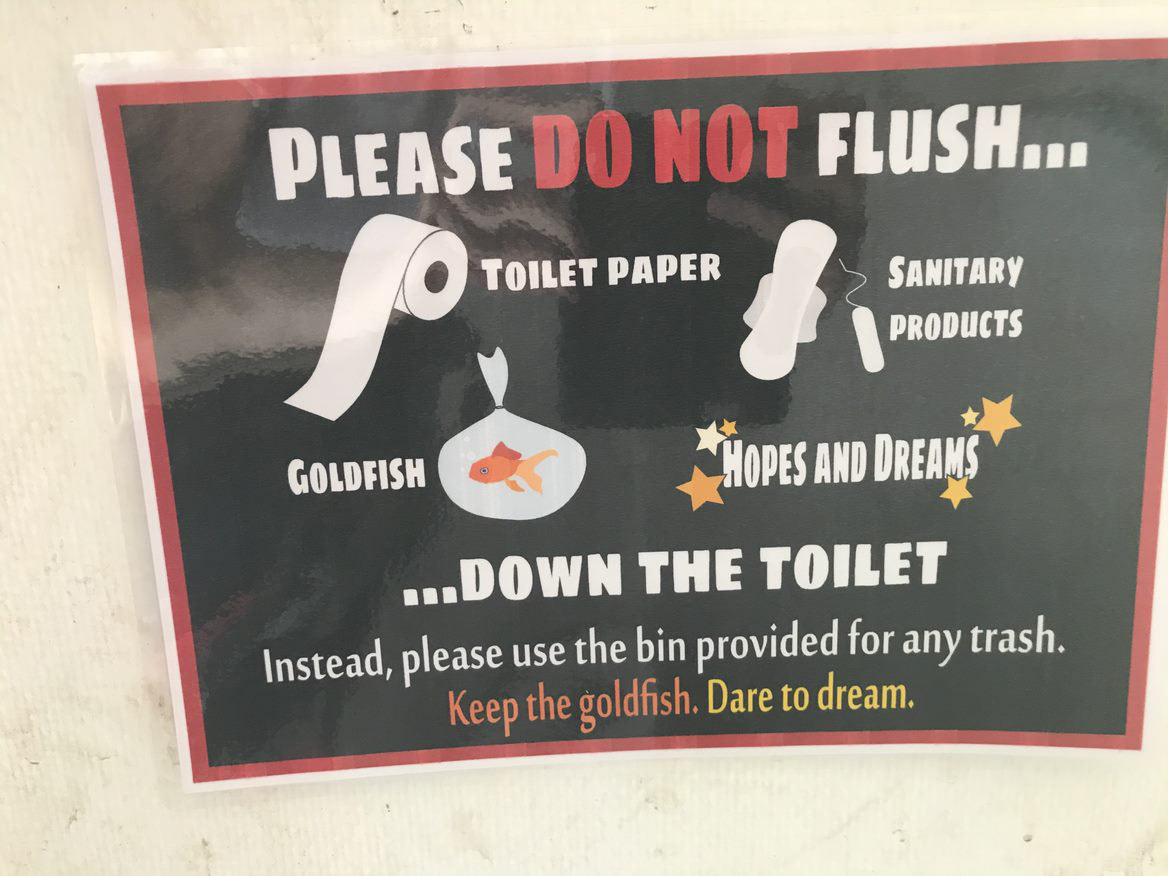

(left) One of the stalls at Phnom Tamao selling snacks and souvenirs. (next) A sign encouraging visitors to respect the animals' space and not feed them human snacks. By Aaron Atkins (next) A Wildlife Alliance vehicle with the Rescue Hotline number. (right) This sign just made me laugh. At many toilets in Cambodia, you are asked to throw away toilet paper instead of flushing it, because the plumbing cannot handle all the paper. We saw quite a few creative signs during our stay. I resisted throwing my hopes and dreams into this one at Phnom Tamao. By Michelle Rotuno-Johnson

About 100 people a day come to Phnom Tamao, Niki estimated -- and a vast majority of these are Cambodian families.

Here at Phnom Tamao and across the country, activists are fighting to curb littering. WIldlife Alliance members try to encourage park visitors to throw their trash away, and Niki said eventually the group wants to make the park plastic-free.

“Countrywide, I don’t know the solution,” she said. “There’s education that’s going on and I have seen Cambodians in their 20s really pushing . . . they seem to be getting it. The entire country, I think that’s going to be a hard one.”

(top left) A clouded leopard, one of the shyer big cats. (top center) Reap the leopard comes up to say hello. She was rescued from a zoo in Siem Reap. (top right) One of the many wild monkeys that live in the sanctuary. (bottom left) Wild pigs take a swim. (bottom center) A golden jackal surveys its territory. (bottom right) A common palm civet climbing a tree branch in its enclosure. By Aaron Atkins

The Wildlife Rapid Rescue Team has saved more than 72,000 live animals in the last decade, seized 54 tons of animal body parts, and arrested about 3,400 traffickers. Wildlife Alliance and the Cambodian government started this law enforcement team in 2001.

Of course, fighting for wildlife does not just mean stopping poachers and illegal dealers. It means educating the public about protecting their natural resources -- from adults down to young children. It means patrolling the Cardamom Rainforest 24 hours a day to crack down on illegal logging and land encroachment. It means working to rejuvenate the rainforest and giving farmers in the area new opportunities for income. And, as Aaron and I saw firsthand, it means caring for the animals at Phnom Tamao.

I left that day exhausted, excited, and a little sad. As I noted, humans are both the cause of, and the remedy for, the suffering these animals endure.

The care of the animals at Phnom Tamao alone is a round-the-clock job, not to mention everything else Wildlife Alliance and Save the Bears do on a daily basis. The task seems so daunting to me. It is easy to “talk the talk” and say you want to help the animals. It is easy to shake your head in disgust when you read an article about poachers being arrested. But to “walk the walk” is an elephantine task, if you will permit me a bit of wordplay.

As I write this in summer 2019, the Amazon Rainforest has been burning for weeks, threatening millions of animals and plants that are crucial to the world’s ecosystem and hundreds of indigenous tribes who live there.

Thinking of the fires in the Amazon and of the animals I met in Phnom Tamao, I am again overwhelmed by the amount of effort, research, money, and work it takes to try and reverse what other human beings have done to this planet.

But, I am encouraged by people like Niki, who dedicate their lives and careers to protecting these animals and their habitats. I am encouraged by the Cambodians working nonstop to preserve their country’s biodiversity. I am encouraged by Chhouk, Sakor, Jamram, and Lucky.

After reading this, I hope you are encouraged, too.