GLC students listen to the audio tour at the entry of Choeung Ek, the Killing Fields. By Delia Palmisano

By Michelle Rotuno-Johnson

REMEMBERING

Just through the gates of Choeung Ek, a large banner in Khmer and English hangs between two trees: “Preserving and conserving evidence is to prevent genocide from re-happening on Earth.”

Behind it is another: “Visitor is the basis of preservation and conservation of Choeung Ek for future generations.”

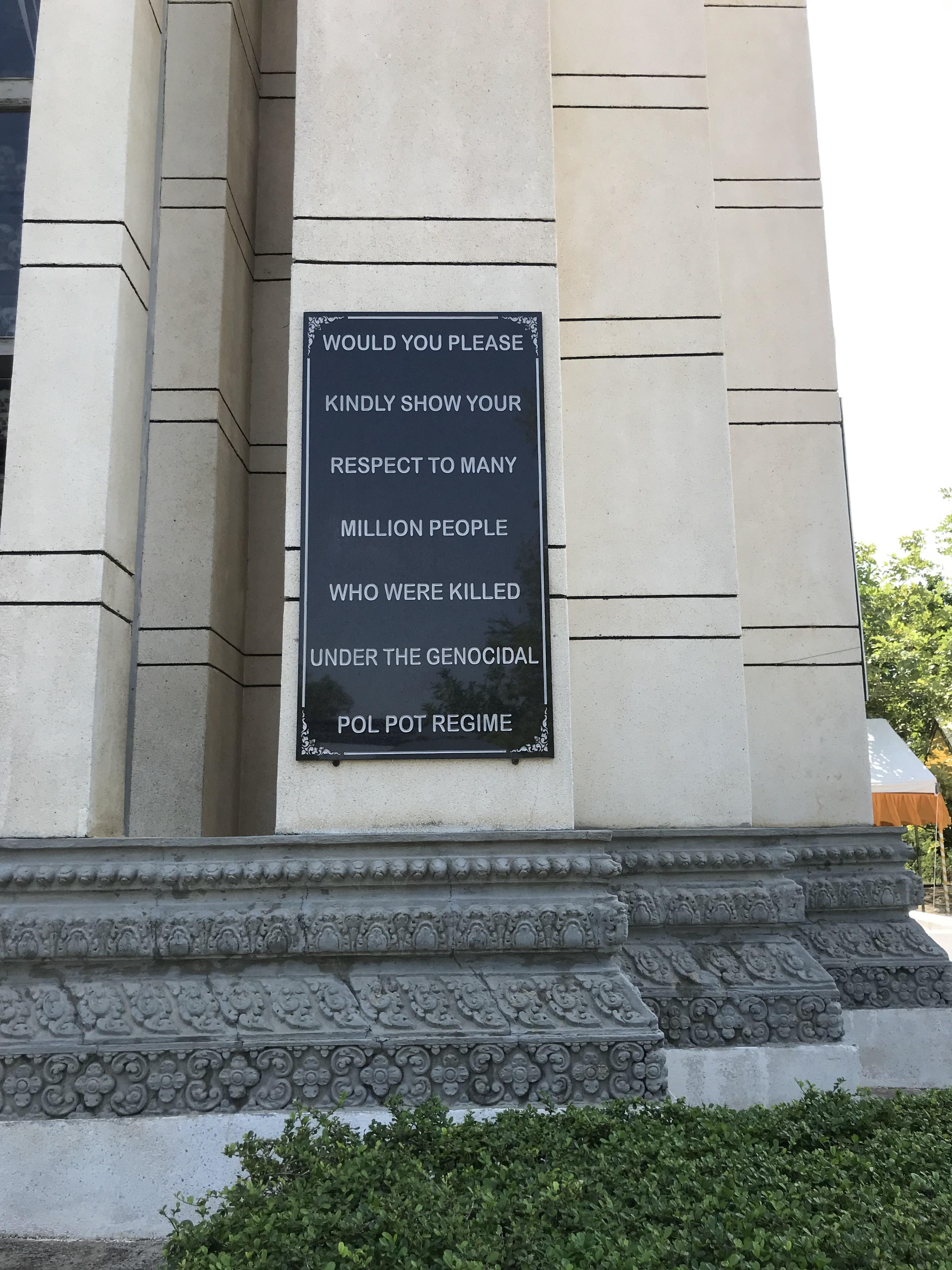

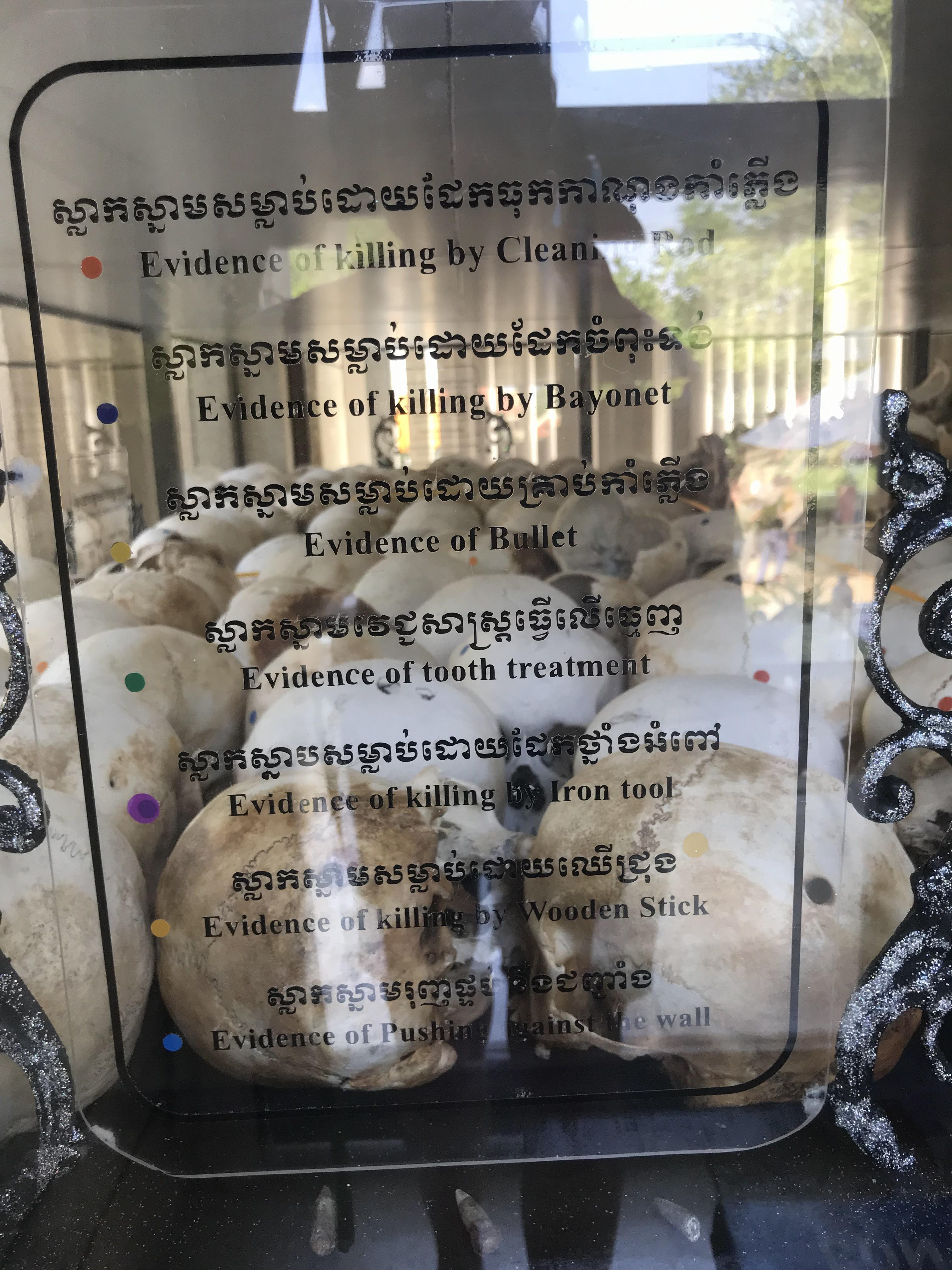

(top left and bottom) Signs indicate the atrocities that occurred at this location and in Cambodia as a whole during the rule of the Khmer Rouge. (top right) At the center of the modern-day Choeung Ek is a memorial stupa (Buddhist monument). Visitors light incense and bring flowers, food, and drinks for the dead. By Michelle Rotuno-Johnson

The message is clear here: The atrocities of the Khmer Rouge regime were horrific. But, if Cambodians and non-Cambodians alike do not stare that horrifying time in the face, it may be forgotten, or swept under the rug, or diminished. Forty years is not a long time, after all. The pain of it feels close here, as you walk slowly around the memorial.

THE LAST STOP

Choeung Ek is one of hundreds of sites around Cambodia where Pol Pot’s soldiers executed people and threw their bodies into mass graves. An estimated 13-17,000 people were killed at Choeung Ek, a former village and orchard about 17 kilometers south of Phnom Penh.

Many of the doomed prisoners came from Tuol Sleng, and would arrive in groups after it got dark. Then, they were marched to a ditch or pit, ordered to kneel, and killed with either a blunt or sharp object -- Khmer Rouge leaders deemed bullets too expensive.

(top left) Marissa Miller, a GLC student listens to the audio tour. (top right) Signs indicate the atrocities that took place in each location. (bottom left) To this day, bone fragments and pieces of clothing are visible around the site. Over the last 40 years, heavy rainfall has slowly washed away the soil, unearthing the remains of people who were buried without marker or name. (next) Each victim’s skull is arranged by age and gender and has a marker, designating how he or she was executed. (next) A glass contains teeth that were found afterwards from the victims. (bottom right) Inside the stupa, hundreds of skulls are displayed behind tall panes of glass. By Delia Palmisano and Michelle Rotuno-Johnson

Visitors have the option to take an audio tour, where the voices of a former Khmer Rouge soldier and several survivors of the regime describe the horrors that happened here forty years ago. Here, where it is bright and sunny and peaceful, and workers are putting up colorful decorations for an event the next day. Here, where a pregnant dog lazes in the sun and people leave water bottles in the middle of the grass.

A pregnant dog stretches out on a hot day. By Michelle Rotuno-Johnson

SOUNDS OF THE TREES

In another time, the trees at Choeung Ek bore fruit. Now, they hang heavy with memories. What could they say if they could speak to us?

A placard at the memorial site identifies a “Magic Tree” where soldiers hung a loudspeaker to drown out the sounds of people being killed.

At another tree, thousands of people have hung bracelets, beads, and other items for children who were beaten to death against its trunk.

Visitors place ribbons, bracelets and other items at the place where women and children were beaten to death at the hands of the Khmer Rouge. By Delia Palmisano

Under a third tree, the OHIO students met Soun Sre Youn, who carries on the Buddhist art form of smot, a style of chanting that has been around for hundreds of years.

Through an interpreter, she explained how there are not many smot singers alive today -- she and a master singer have been teaching young girls the art. Smot is usually performed at weddings and funerals, Soun said, but lately people use recordings instead of hiring one of the few singers trained in the art.

Video by Russell James

MORE INFORMATION ON THE CAMBODIAN GENOCIDE:

The Genocide Studies Program at Yale University partnered with the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) on a decade-long project to document mass graves, former prisons, and genocide memorials in the country.

They discovered 388 mass grave sites and 196 former prisons run by Pol Pot's soldiers, and 81 genocide memorials built by survivors of the Khmer Rouge rule.

They also documented 115,000 sites targeted by the United States from 1965-75. Combined, the Johnson, Nixon, and Ford administrations dropped at least half a million tons of munitions

on Cambodia.

on Cambodia.